Carnegie Mellon University | 2022

Smart Chess Board

Real-time load localization using distributed load cells and embedded signal processing.

Context

This project investigated whether a small number of distributed load cells could be used to infer both the magnitude and location of loads on a planar surface, without relying on vision-based sensing. A chessboard was selected as a constrained, interpretable test case where discrete object placement and movement could be evaluated quantitatively.

The work was completed as part of 12-778: Sensors, Circuits, and Data Interpretation for Infrastructure Systems at Carnegie Mellon University (Fall 2022). The course emphasized end-to-end sensing systems, spanning physical measurement, signal conditioning, calibration, uncertainty, and embedded data processing.

Beyond the chessboard demonstration, the broader motivation was to explore load localization as a general sensing primitive, applicable to assistive interfaces and infrastructure monitoring scenarios where low-cost hardware and robust inference from noisy measurements are required.

Approach

The system models the chessboard as a rigid plate supported at four corners, with one load cell at each support measuring the reaction force. Rather than sensing individual squares directly, the approach infers object location by analyzing how a point load redistributes across the four supports.

This reduces the localization problem to two coupled one-dimensional calculations along the board axes. By decomposing the total measured load into orthogonal components, the position of a weight change can be computed analytically from the relative changes observed at each load cell.

Embedded firmware on a Raspberry Pi Pico W continuously sampled the four load cells through HX711 amplifiers, applied averaging to suppress noise, and detected load changes exceeding a calibrated threshold. When a change was detected, the firmware computed the corresponding coordinates and mapped them to a discrete 8×8 grid matching the chessboard layout.

This model-driven approach allowed position inference without dense sensor arrays, cameras, or external tracking, relying instead on calibration, signal conditioning, and mechanical reasoning.

Implementation & Tools

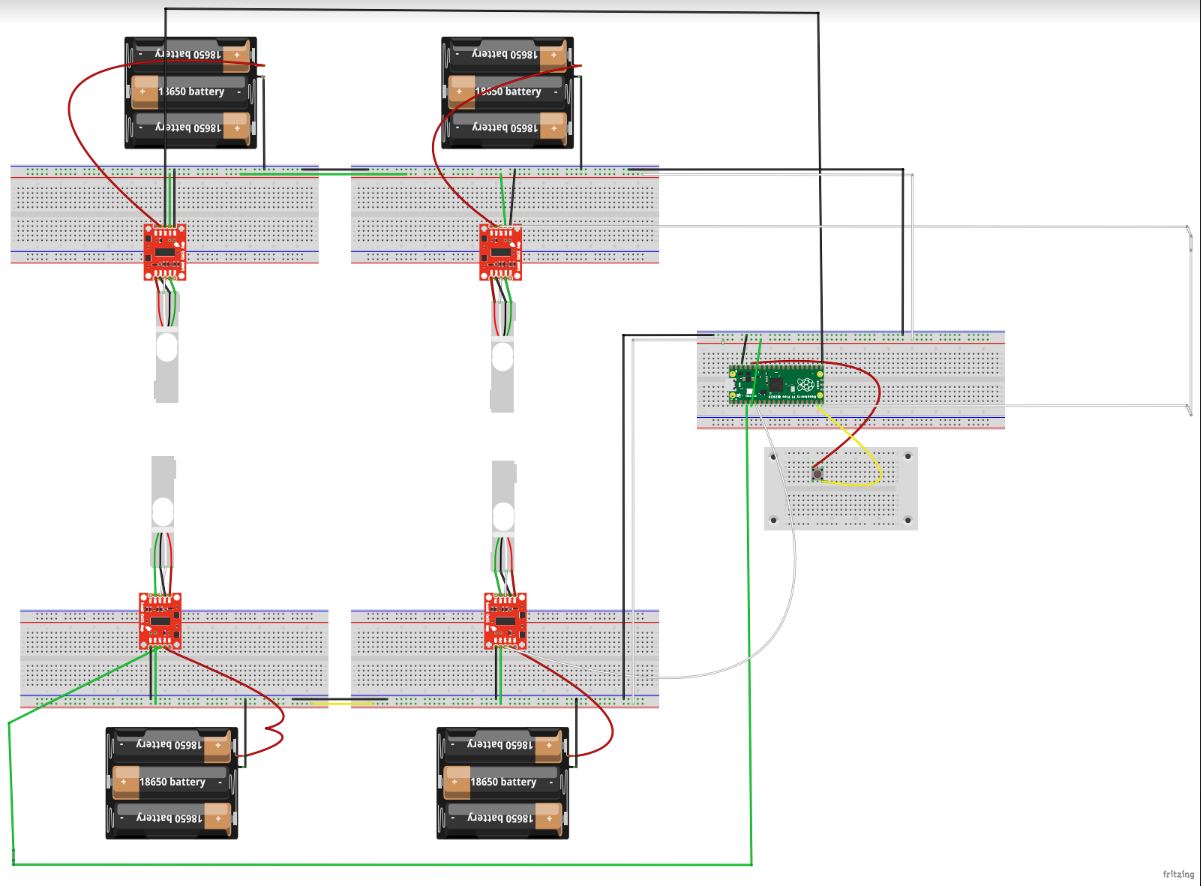

- Four 5 kg load cells mounted at the corners of a custom-built wooden frame, supporting a rigid 22×22 inch chessboard surface.

- HX711 24-bit ADC modules used for signal amplification and digitization, providing sufficient resolution for detecting small weight changes from individual chess pieces.

- Embedded firmware on a Raspberry Pi Pico W responsible for synchronized sampling, moving-average filtering, threshold detection, and coordinate computation based on calibrated load distributions.

- Linear calibration routines implemented per load cell using known weights, with tare compensation to remove the board and resting piece mass from subsequent measurements.

- A lightweight Python serial interface used during development to stream data, validate calibration curves, and verify localization behavior during bench testing.

Key Results

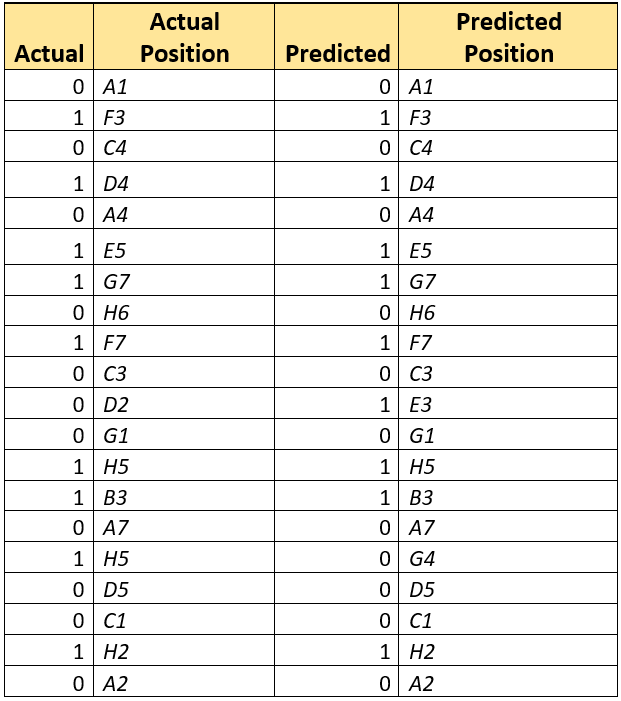

Following per-sensor calibration and tare compensation, the system correctly localized single-piece placement and removal events across the board with approximately 90 percent accuracy over 20 controlled trials spanning multiple grid locations.

Reliable detection was achieved using a 10 gram threshold and short-window averaging, allowing the system to suppress sensor noise while maintaining responsive updates during piece movement.

The results validated that sparse corner sensing, combined with an analytical load-distribution model, is sufficient for discrete position inference without dense sensor arrays or vision-based tracking.

Analysis & Insights

The dominant source of localization error was not sensor resolution but mechanical and modeling assumptions. Small deviations from ideal rigid-body behavior, including uneven support contact and slight board compliance, produced asymmetric load redistribution that affected position estimates near grid boundaries.

Temperature drift and long-term sensor bias were mitigated through frequent taring and short-window averaging, but these effects highlighted the limits of purely static calibration in low-cost sensing systems. The system performed best when inference relied on relative load changes rather than absolute weight values.

From a system-design perspective, the project demonstrated that analytical modeling can meaningfully reduce hardware complexity. By leveraging load-distribution physics, four sensors were sufficient to solve a problem that would otherwise require dense instrumentation or external perception.

What This Demonstrates

- Ability to translate physical intuition into analytical models and deploy them in embedded systems, a skill directly applicable to sensing, controls, and inference problems.

- Experience leading end-to-end technical work, from problem formulation and modeling through firmware implementation and experimental validation.

- Comfort operating at the boundary between theory and implementation, including calibration, uncertainty, and robustness considerations.

- A bias toward reducing system complexity through modeling rather than adding hardware, reflecting disciplined engineering judgment.

- Transferable foundations for work in infrastructure monitoring, physical analytics, and quantitatively driven decision-making roles that require reasoning from noisy measurements.

Artifacts & Links

- Full group project website — extended methodology, figures, and documentation

- Firmware and data acquisition code

This project was completed as a four-person team as part of 12-778 under the supervision of Prof. Mario Bergés. My contributions focused on the system concept, load-distribution modeling, and embedded firmware development, working alongside teammates who contributed to testing, documentation, and supporting analysis.

Team members: Ishwrya Achuthan Geetha, Sakar Adhikari, Sri Ramana Saketh Vasanthawada.